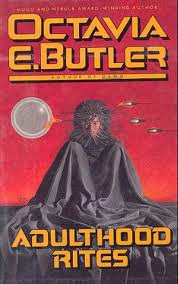

Second in the Xenogenesis trilogy, this book is just as good as its predecessor and whets the appetite for the third, Imago, with ease.

Butler's deceptively simple style and short chapters make the characters relatable and the action continuous, even as the story spans many years.

This book, as well as the first, Dawn, sidles up to the idea of what it is to be human, how identity is created, and what (if any) ethical obligations exist in the face of pure biology.

I also found that reading it and identifying with characters with such broad perspectives has affected my own attitude in dealing with others and making decisions on a daily basis.

For one thing, patience is a highly prized characteristic of the "noble" characters in the book. It is also what the feared alien race is known for emulating to an almost ridiculous degree. It is often impatience that drives the human characters to exhibit the worst of their species - frustration, insecurity, aggression, paranoia. All these traits arise when humans are unable to take the time to merely listen: not something that requires decades of dedication. It is their unwillingness to listen to or put trust in not only the aliens, but others of their own species, that lead them to display the exact behavior which has convinced the aliens that humanity is incapable of survival without "genetic trade."

The brilliance of Butler's writing is multifold, but I am most particularly impressed with how ironically humanized the alien characters and psychology are as this story unfolds.

At the start of Dawn, identifying with the protagonist Lilith was simple and smooth. Butler rolls out information about the Oankali to the reader at the same speed Lilith receives it, and as a reader I found myself going through similar anxieties and doubts.

By the middle of Adulthood Rites, what could be called the "superiority" of the Oankali is difficult to dispute in many ways. Although unmoved by emotional displays and slow to make decisions, they do ultimately choose to do the "right" thing by human standards, at least to the degree that the situation allows. Humanity, meanwhile, continues to splinter and argue rather than accept their situation or make due with a compromise.

This was also a theme I picked up on in Butler's phenomenal novel, Kindred. Acceptance of an unfair and brutal reality. Patience in the face of dangerous opposition as unstoppable as a force of nature, but embodied in human form.

It is impressive that a story with such a preposterous premise is able to carry within it serious doubts and relevant assertions regarding the value of our very own species. Although the Oankali offer their trade to humanity on a genetic and cellular level (curing disease, improving memory, and the like), it is worth considering what other qualities they display that we are capable of learning within the genetic structure we already have.

It is disheartening to think how realistic it might be that extraterrestrial interbreeding may be the only thing that is capable of saving humanity from destroying itself. And yet, using borderline cartoonish alien creatures as facilitators, Butler brings this possibility into palpable consideration while at the same time displaying the respect and empathy for the undefinable humanity that each of us inexplicably carries on a level that transcends genetics.

Friday, January 3, 2014

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold

It took me about two and a half days to read this book, and those were days during which I had plenty of other things to do. What I'm saying is, it's a very quick read. It was easy to read, which may explain some of its "astonishing" universal appeal.

It is difficult for me to really latch onto whatever the amazing bestseller list creators of this world latched onto when they ate this book up. I do not have children, nor do I have friends with children. I was fourteen years old just over a decade ago, and I certainly wasn't one in the 1970s with a nice loving family appropriate to that decade. I have not encountered murder, never known anyone who was murdered, or of any friends of friends who were murdered. I have watched a lot of Law & Order.

And that's what this book felt like, in a lot of ways. It trades on its dramatic irony too heavily for my money, as you know the killer and the details of the protagonist's death within the first chapter or two, I was primarily interested in if the man would be caught and how and so forth. Sebold focuses instead on the family dynamics and some intrapersonal dynamics that develop after the protagonist is killed. That is all well and good, but for my money her characterizations are not particularly engaging or thrilling. There are effectively sentimental or insightful moments, but nothing that challenged me to think differently.

Perhaps that is this book's strength, and a source of its popularity - it never really REALLY challenges you in a significant way. Sebold describes things well, if something erring on the side of purple prose, and it can be very powerful to have an unreliable narrator who is also omniscient? But overall, I just couldn't go with this book. Parts of it were really interesting, but there are some spoiler-related plot twists that I did not care for at all, that sustained the feeling that I was watching an episode of Law & Order that was trying to wind everything up in the last 12 minutes of showtime.

I didn't dislike this book, but I also didn't love it. I thought about not finishing it, but I finished it if only because it was so easy to do so, so easy to read and digest. I can see why it would get picked up to be made into a movie, but I also wonder how they will be able to commit it to film without making it REALLY cheesy.

I could see myself encountering someone who loved this book intensely that I already don't like, and getting into an argument about the book's merits. But I have not met that person yet. As it stands, this is mainstream packaged writing, very sentimental, very manipulative, very straight-forward, very traditional but with a "new" narrative twist and some versions of heaven that are palatable to today's am-I-or-am-I-not theist intellectual. I felt somewhat pandered to while reading this book.

There are better things for me to read, but there are also much worse things that the public in general could be reading. After all, you can't really beat up a book whose main themes include love, recovering from pain, learning to live, blah blah. Those things are universally appealing, they apply to all age groups, all social groups. Perhaps that is what stopped the book from engaging me, it was TOO universal in that way.

Also, most of the writing was not particularly impressive. I got the feeling that I was reading something that I could have conceived of and written. Yes, it's true that I did NOT conceive of or write it, and that Sebold did, so who am I to criticize - yes, that's all very true. But I enjoy books the most when they seem to be these messages sent across time and space by a person who artistry is somehow magical to me. How could Frank Herbert write Dune? I couldn't do it. Too much vocabulary, too much planning. I couldn't write even something like Blindness, another book I wasn't crazy about. But I couldn't have written it, or have come up with the idea. So good for them.

As for Sebold, I don't know. I guess this means she is a very accessible writer, and whether that is a good thing or not depends on each individual reader. I like to work a little bit, or have my notions about things twisted around, and so forth. I am not everyone.

I'll admit that amongst the many bits of sentimentality in The Lovely Bones, there were some that struck a cord and remained. I would never begrudge Sebold that. She succeeded wonderfully in a type of writing that I just don't particularly care for.

The end.

Friday, August 14, 2009

Dune by Frank Herbert

You can imagine, already, that my impression of this book is very favorable, as I have read many things between my last entry here and Dune, and although a few have gotten close, none have actually pushed me back into an update.

Several weeks ago, I watched David Lynch's 1984 film adaptation of Dune. I was already on the verge of deciding to try out some fantasy or science fiction novels, I'd pretty much run my course with crime novels and cheeky fiction for the time being, and was feeling a bit bored and frustrated by what was available to read. The book I had read most recently was The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood, which is a fantastic if emotionally draining book. I was beginning to worry that if I wanted to keep being impressed by what I read, I would need to suffer along with the characters I was interested in.

Science fiction is a genre that many people have told me I would love, and I have resisted reading it (with the exception of some Star Trek novelizations when I was in middle school, yes, there, I said it), for a couple of reasons. One is that it seemed intimidating - there'd be a whole slew of new vocabulary to learn and it was possible I'd have to actually know a little science, or be used to thinking in scientific terms, in order to follow the action of the book. I was hesitant despite the recommendations of my most trusted literary friends. I figured I'd put it on the back burner and it would be one of those genres that I'd get into when I was much much older. As it turns out, that honor will probably be reserved for extremely long tomes of classic fiction and/or biographies, because, hey, Dune.

As I was saying, I watched Lynch's film adaptation recently and, in addition to being thoroughly confusing, was very taken in by the basic ideas and aesthetic of the film. The dialogue, though cheesy, was very appealing to me for some reason, and the trick of having the audience hear the characters' thoughts via voiceover was one of my favorite narrative tricks. But this isn't about praising the movie. It is merely worth mentioning that the movie was intriguing enough for me to decide, yes, it is time to read a science fiction book and, yes, Dune is going to be it.

After a little searching (the library did not have a copy), I obtained a beat-up paperback of the novel (my favorite kind of book to read), and set to work. Almost immediately, I fell in love with this book. The dialogue remained cheesy, the effect of knowing the characters' thoughts in addition to their dialogue is achieved with the use of italics, and so forth.

Every section begins with a quotation from a number of documents regarding the protagonist that were written after the events of the book take place by a Princess Irulan, who does not appear until the end of the novel and even then has very little character. She gives us little snippets of legend and lore to carry us along, but the little attention she gets at the end of the book goes a long way, and you can see an actual personality poking out behind those quotes, stopping it from feeling like a cheap narrative trick.

A friend of mine made the mistake of asking me, "What is Dune about?" This proved to be a very difficult question to answer and I'm not sure I can do it here, either. It's about planetary evolution and preservation, it's about the politics of environmental resources, it's about gender, it's about the frightening power of religion and how easy it is to manipulate both religious text and practice for better or worse. It's about expanding consciousness, attempting to avoid war, it's about love versus duty, it's about the nature of friendship and the method by which one can negate potentially long hours of political negotiations. Oh, and gigantic worms that live in the sand, did I mention that?

Most of the action takes place on a desert planet, Arrakis, and the largest framework involves the struggle for control of this planet between the Emperor and two major Houses - one led by a Harkonnen Baron and one led by an Atreides Duke, Leto. Leto leaves his home planet, the water rich, earth-like Caladan, to assume control over Arrakis, which is currently ruled by the Harkonnens.

Arrakis is inhabited by a native population called Fremen, who have adapted to living on a desert planet in surprisingly and somewhat disgusting ways. Arrakis is the only location in the universe where spice melange exists, which is what makes space travel possible. The spice melange also functions as a drug in various forms, which is used by all sorts of people.

Paul is Duke Leto's only son, born to him of his concubine Jessica, and the protagonist of the story. The majority of the action involves Paul being stranded on Arrakis with his mother, adapting to the Fremen ways, and essentially becoming their prophet.

One more interesting thing is that, in this universe, computers and other "thinking machines" have been outright banned, and in their place, human beings are trained to use their full mental potential. Different sects are trained in different ways for different purposes - the Mentats are human computers frequently employed as assistants to those in power and are male, but there is also the clan of the Bene Gesserit, all trained in somewhat more passive ways, all women, their goal to recreate a kind of genetic engineering by strategically copulating and procreating with particular bloodlines. And by passive, I do not mean these women are powerless - they are called witches with some regularity, and are capable of extreme manipulations due to their ability to observe minutiae about those around them and the training they receive to control their own bodies and minds down to the slightest muscle, down to the ability to reconfigure the chemical structure of a poison so that it can be metabolized by their body without harming them.

Phew, there is just so much that I could continue on explaining without ever getting to an actual review of the book.

The Bene Gesserit are, for my money, the most interesting part of the book. Not all, but most of what they do, is conceivably within human reach, and so their existence serves as a reminder to the reader of what a human being is truly capable of. If we didn't keep all of our information inside glowing boxes and never actively think about it, we could be unstoppable. A test administered by the Bene Gesserit is that of the gom jabbar. The testee places their hand inside a mysterious box while the test administrator places a poisoned needle (that's the gom jabbar) at the test taker's neck. The administrator then applies psychological tricks and influence to convince the taker that the hand inside the box is undergoing extreme pain. The taker believes this to be reality, they can feel their flesh burning in agonizing horror. However, if they remove their hand from the box, they will be stabbed in the neck with the poisoned needle and die. This is a test used to determine whether a person is an animal, or a human. The distinction is, if you can act against your own self interest, which implies a sense of reason that is stronger than that of instinctual self=preservation, then you are human.

The book is full of things like this - statements about humanity, the nature of fear, the notions of future and past, etc., that are coached inside silly vocabulary and outlandish situations, yet retain a kernel of almost universal truth, or otherwise intriguing, broadly sketched out notions. Almost all of those notions resonated strongly with me, and I found myself easily accepting the ridiculous vocabulary that was an initial reason for me to reject this genre straight out. Fine, I feel a little silly when I go on a rant about the Water of Life and the gom jabbar, and the differences between when Paul is referred to as Paul, or Usul, or Muad'Dib, but WHATEVER.

This novel, though hefty, was a quick read. It's simply written, the sentence structure is very basic, Herbert does a great job of being accessible to his audience. The italics that mark different characters' individual thoughts work to add a fantastic layer of tension to a scene - each character seems more alive as you can read their exact thoughts and not an approximation (such as, "Jessica felt sad, or Jessica knew that her son was unprepared for the fight"). The difference is subtle and ingenuous. His breakdown of the book into sections using Irulan's quotes is also very helpful, as it means you can take a break every three or four pages, and yet he still has the book organized into three large sections. The vocabulary may be intimidating (even screenings of the movie involved glossaries, and the book has a few appendices in addition to a glossary), but if you are the same kind of reader I am, you'll never need to use those. Almost all of the words are easy to define for yourself using context, as they are repeated or explained within the text. It's not exactly A Clockwork Orange in terms of expecting you to adapt to an entirely new way of thinking.

To go back to its film adaptations - I know there is another one in the works, and that a Sci-Fi miniseries was done in 2000, and I am intrigued by both of these projects. However, I feel as though the best aspects of Dune are unfilmable. The action could be fantastic (Paul kicks one of his captors between the ribs and shatters his heart's right ventricle, and so forth), but the layers of tension within those fights (knowing the characters' thoughts, having the subtle meanings of each fighting gesture explained and contextualized in an abstract way) will never get across.

For example: a character named Feyd fights a gladiator-slave at one point in the book. Feyd is the Baron-to-be and wants to start taking control from the current Baron as soon as possible. Slaves in these fights are normally drugged (although this is the only fight we see in the narrative, so this fact is told to us directly). The drug would turn their skin green and put them in the grips of terror, making them easy to defeat. Feyd wields two blades - one long, one short, the longer one usually tinged with poison along the blade. The tradition would be to slay the slave with the poisoned blade, if possible, and then point out the effects of the poison on the slave as it takes him over to the cheering crowd. In this instance, Feyd has struck up a plan to fight an undrugged slave (skin painted green) so that he can accuse the Baron's slavemaster of incompetence and place a main of his own in that station. As a precaution, however, Feyd has had the slave hypnotized, so that if he utters a word ("Scum"), it will cause the slave's muscles to all suddenly constrict and freeze up, making slaying him very easy. Also, as Feyd does not trust anyone, he has tinged his short blade with poison instead of the long one, so as to confuse the gladiator slave (who will have his wits about him). THAT IS A LOT OF INFORMATION TO COMMUNICATE IN A FILM. It is all important for the tension of the scene, yet it's much easier and faster to read than it would be to watch.

Although a flop, it's worth noting that Lynch's Dune nailed its production design right on the head. The world Herbert describes is strange, its aesthetic is very specific, and the makers of 1984's Dune really did an amazing, amazing job. I know it received Herbert's seal of approval in that regard.

I have another science fiction book or two lined up, but it is not time yet. I am still stuck on Dune, very impressed by it, etc. It is worth reading the Wikipedia entry on it, as its historical significance (particularly being the first "ecological" science fiction novel) is extremely interesting in its own right.

This entry is messy and overly long, but its whole point is to get me back into writing here, so forgive me and it may pay off in the end.

Tuesday, December 16, 2008

She by Robert A. Johnson

I first read this book at roughly the same time last year, and I found that revisiting it was worthwhile.

This is a book subtitled: Understanding Feminine Psychology, and it is Johnson's explanation of the feminine psyche (in both men and women) using the myth of Eros and Psyche.

There isn't much to critique from a book like this, but it has some personal significance to me, so I will make a few comments.

I did not consider myself a Jungian in any sense of the word prior to reading this book, and was in fact highly skeptical of dream analysis or mythological comparison having any usefulness in my daily life. I would not say that Johnson's book radically or suddenly altered my opinion: when I first read it I completely neglected the dream analysis portion of the back of the book, and scoffed at certain chapters. Much of it reads like a self-help book in the abstract - the "lessons" of the myth are frequently as simple and cliched as "take things one at a time" or "maintain perspective lest you get lost in insignificant and overwhelming details," etc.

These certainly work against the book as a piece of literature, and I am not sure what redeems this book for me. It may be that its very simplicity is welcome. In the face of heavy and complex literature, it might be a good idea to remind oneself that the mythologies much of today's stories draw on are, in fact, quite simple. They require that you, the reader (or listener) apply meaning to them, and it is a fun mental exercise to consider how or why these same stories have survived many generations and floated through different cultures. Such ideas are better addressed in the works of Joseph Campbell, I'm sure, but not everyone wants to start out on that heavy level.

If you have an open mind, and are interested in ways that myths might apply to our modern psychologies, this is a very simple and unassuming place to start. Treat it like a primer. Johnson has also written He and We, neither of which I have read, but I would like to obtain a copy of each soon.

She, in particular, is to blame for a subtle shift in the way I began to think about women and how they interact with men, each other, and themselves. It made me think of personal psychological progress in a different way. And it certainly affected the way I thought about meeting my partner's Mother (believe me, that capital M belongs there).

In other words, although this may fall into a literary category somewhere between storybook and psychobabble, there is inherently nothing dangerous about exploring some of the (admittedly) abstract ways our lives can connect to the lives of gods and goddesses from thousands of years ago. It can infuse meaning, or it can be merely a distraction during your lunch hour. It is an extremely short and simple book, after all.

This is a book subtitled: Understanding Feminine Psychology, and it is Johnson's explanation of the feminine psyche (in both men and women) using the myth of Eros and Psyche.

There isn't much to critique from a book like this, but it has some personal significance to me, so I will make a few comments.

I did not consider myself a Jungian in any sense of the word prior to reading this book, and was in fact highly skeptical of dream analysis or mythological comparison having any usefulness in my daily life. I would not say that Johnson's book radically or suddenly altered my opinion: when I first read it I completely neglected the dream analysis portion of the back of the book, and scoffed at certain chapters. Much of it reads like a self-help book in the abstract - the "lessons" of the myth are frequently as simple and cliched as "take things one at a time" or "maintain perspective lest you get lost in insignificant and overwhelming details," etc.

These certainly work against the book as a piece of literature, and I am not sure what redeems this book for me. It may be that its very simplicity is welcome. In the face of heavy and complex literature, it might be a good idea to remind oneself that the mythologies much of today's stories draw on are, in fact, quite simple. They require that you, the reader (or listener) apply meaning to them, and it is a fun mental exercise to consider how or why these same stories have survived many generations and floated through different cultures. Such ideas are better addressed in the works of Joseph Campbell, I'm sure, but not everyone wants to start out on that heavy level.

If you have an open mind, and are interested in ways that myths might apply to our modern psychologies, this is a very simple and unassuming place to start. Treat it like a primer. Johnson has also written He and We, neither of which I have read, but I would like to obtain a copy of each soon.

She, in particular, is to blame for a subtle shift in the way I began to think about women and how they interact with men, each other, and themselves. It made me think of personal psychological progress in a different way. And it certainly affected the way I thought about meeting my partner's Mother (believe me, that capital M belongs there).

In other words, although this may fall into a literary category somewhere between storybook and psychobabble, there is inherently nothing dangerous about exploring some of the (admittedly) abstract ways our lives can connect to the lives of gods and goddesses from thousands of years ago. It can infuse meaning, or it can be merely a distraction during your lunch hour. It is an extremely short and simple book, after all.

I have been away.

It only takes one comment, sometimes.

Hello. I have been away. Some personal issues and changes in my schedule have unfortunately kept me from updating this journal with regularity. I did not quite realize I was missed, but as that seems to be the case, I will attempt to update soon.

I was reading The Demon Flower when I stopped updating - I never finished the book, and actually found it to be quite dismaying. I have since read bits and pieces of things here and there, but the only entire books I have read are Naked Lunch and Nothing More Than Murder by William Burroughs and Jim Thompson, respectively.

I have begun to work on some writing projects of my own, which has slowed down my reading considerably. This is probably to the detriment of my personal well-being. Hopefully, I will soon be in a position where I have a smoother commute to work, as I do the majority of my reading to and from the office. Currently, I need to transfer buses, which only gives me ten to fifteen minutes of reading time at once, and this is not enough to sustain the mentality required for engaging with a book. My evenings are taken up by sporadic activities, including the sudden disposition to daily journaling, which requires an entirely different mentality from that of reading, a renewed interest in film, and the acquisition of a new boyfriend.

Given all that, I am also currently reading a non-narrative. I am reading The Goddess Tarot, which is nothing more than the explanatory book accompanying a deck of tarot cards a good friend gave to me.

However, I have recently purchased a number of interesting books, and when Christmas break arrives I will make it a point to read at least one of them. For now, I will make a short post on a short unknown book, and then go to bed. Thank you for continuing to read.

Hello. I have been away. Some personal issues and changes in my schedule have unfortunately kept me from updating this journal with regularity. I did not quite realize I was missed, but as that seems to be the case, I will attempt to update soon.

I was reading The Demon Flower when I stopped updating - I never finished the book, and actually found it to be quite dismaying. I have since read bits and pieces of things here and there, but the only entire books I have read are Naked Lunch and Nothing More Than Murder by William Burroughs and Jim Thompson, respectively.

I have begun to work on some writing projects of my own, which has slowed down my reading considerably. This is probably to the detriment of my personal well-being. Hopefully, I will soon be in a position where I have a smoother commute to work, as I do the majority of my reading to and from the office. Currently, I need to transfer buses, which only gives me ten to fifteen minutes of reading time at once, and this is not enough to sustain the mentality required for engaging with a book. My evenings are taken up by sporadic activities, including the sudden disposition to daily journaling, which requires an entirely different mentality from that of reading, a renewed interest in film, and the acquisition of a new boyfriend.

Given all that, I am also currently reading a non-narrative. I am reading The Goddess Tarot, which is nothing more than the explanatory book accompanying a deck of tarot cards a good friend gave to me.

However, I have recently purchased a number of interesting books, and when Christmas break arrives I will make it a point to read at least one of them. For now, I will make a short post on a short unknown book, and then go to bed. Thank you for continuing to read.

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

In Praise of Barbarians: Essays Against Empire by Mike Davis

It took me a good long while to get through this book of essays. There is only so much really depressing socialism I can take at any given time.

Here, I'll sum this book up for you. "You think things are bad? Well you're wrong. They're TERRIBLE. I'm Mike Davis. *very dry joke that's almost impossible to laugh at given the circumstances of the world you've just been made aware of*"

Don't get me wrong. I like Mike Davis, even though I understand there is an anti-Davis element in the literary world that accuses him of being too dour and twisting the facts to fit his apocalyptic socialism-fueled views of the world.

It's good to realize that the problems of this country, and this world, and far deeper than just "some of us like Jesus and some of us don't." There really are systematic problems that have become bigger than any particular individual and therefore require an equally organized response.

Unfortunately, Davis doesn't seem entirely hopeful about a counter-organization. So each essay is sad and terrible and hopeless. That's why it took so long for me to read the whole thing. I couldn't possibly read it all in one sitting without jumping off a bridge and/or annoying the shit out of my friends.

There are a lot of interesting facts in this book, but unfortunately I have neither the patience nor desire to check up on their veracity. By the end of the book, I felt that doing so was necessary to make any informed review, because without the facts at hand I can't analyze Davis's slant. Are things really that bad? Really?

Davis clearly identifies with the underdogs in every scenario he describes, which is all well and good, but by the final pages it feels like the identification is compulsive rather than informed. I can't attack the man personally, I can only talk about my impressions of the book.

For example, the essay on the Sunset Strip "riots" showed a clear willingness on Davis's part to believe that teenagers are, on the whole, calm. He cites the cost of their property damage as if to assuage our fear of chaos. Teenagers don't need to smash anything to make adults nervous. Put one too many teenagers on a public bus and you can feel everyone's heart rate rise. And those teenagers aren't even protesting anything. No, I don't side with the police, and in the instance of these "riots" I have to side with the teens on principle. As Davis describes it, this is an incredibly fascinating event that I didn't even know happened.

There's a lot of that "I didn't even know that happened" feeling radiating from this book, and on that level I recommend it. But maybe in bits and pieces.

Monday, June 16, 2008

Moral Disorder by Margaret Atwood

I've decided to start adding pictures of the books, if I can acquire images of the correct editions. For example, this is the paperback cover, which is so much more . . . paperbacky than the original cover, as you can see:

Anyway, this book had been waiting patiently for me to read it. At first I thought I didn't have anything to say about it, although I enjoyed it immensely, but as I plumbed deeper into my own thoughts, I realized the exact opposite.

Many of the other books I write about have all this STUFF surrounding them. Of Mice and Men for example, is on the way. There's some amount of clout to them, whether it comes by way of critical recognition or mere shock value. I don't usually look at something, think to myself, "Oh this looks pleasant" and then get right down to it. You can ask Schrodinger's Ball, whose lime green cover and promises of mild intellectual challenges have been collecting dust at the floor near my bookshelf since late March while I passed it over for more frantic flights of fancy, again and again.

I also don't react well to clout, at times. This is why Siddhartha is bound to be neglected for awhile, and so on.

So why pick up Moral Disorder? Lately I've been drawn to short stories - in the past I was skeptical of short stories as art forms, don't ask me why, I guess I just didn't like what felt like a middling ground between poetry and novel. Lately, however, short stories have been all the rage for me.

I know a smattering of Atwood's poems outside of the collection Power Politics, which I know by heart and count as a personal influence in my own creative writings. So I surprise even myself by realizing that it has taken me this long to read any of Atwood's complete sentences. Maybe the titles of her books were just too daunting, or I was afraid I'd be getting into some overly poetical fiction, like I felt about A Spy in the House of Love. Short stories? Nice stopover to decide if I'm actually ready to try tackling the other novel of Atwood's I have sitting around, Surfacing.

Of course, none of this has to do with the book itself. The book is a collection of short stories that all center around one character, sometimes written in first-person, sometimes in third-person, perspective. She is a child in one, an adult in another - she is overshadowed by her parents, but then outlives them. Etc.

Atwood's writing is perfectly opaque. What she presents requires no interpretation, no reliance on outside philosophies, no comparison to other works. She writes so directly that I couldn't help but wonder if I was reading her diary or, at times, long-forgotten entries from my own diary.

This is the sort of thing that I always loved about Bukowski and, not to conflate the two authors AT ALL, Fante: the presentation of facts, both physical and psychological, were so direct as to be impenetrable. "Here," their works would say, and plop a huge heavy metaphor down on the table in front of you, "this is -how it is-." It is refreshing to read something that doesn't require intellectualism to move you.

But the major fault, if you can call it that (which you can't, I only do so for argument's sake), with these writers is that they are MEN. Their views on women and on themselves can help me understand what I would love to call a general "human" mindset, but unfortunately all they fleshed out was a very masculine point of view. Sometimes, it's easy to forget that there are other realities, because female writers can either be extremely feminine and write only of womanly things like flowers and dewdrops and, I don't know, Tampax or whatever. OR, they can try to adopt a more masculine genre, as Ms. Highsmith did. Or, god forbid, they can go in for Chick Lit.

It's an old feminist cry: women cannot be humans the way men can. Men have already set the standard for what is human, what is human experience. In a way, they have done so with books as well. We can choose the male authors who are most sympathetic or reverent of women, or we can go for Virginia Woolf, whose very sentence structure contains the sort of convoluted psychological and emotional superfluity that men are always ragging on women for. Don't get me wrong, I fucking LOVE Virginia Woolf, but she's not "practical" in getting the facts of the story across. The plot, like for many women, is all in her head.

In other words, how can a woman write a woman's life without just being either a reactionary or a lackey to masculine writing? Can she? What are her options? And then what are mine as a female reader in this situation?

What am I going to do to see my life reflected back upon me? Read The Devil Wears Prada? Try to find some modern parables in Jane Austen? What about ME, the intellectual, sexual, observant, creative modern woman who takes herself far too seriously but is still worthy of the respect of practical-minded folk?

There is a story in psychoanalytic circles of a patient who did not know she was cold until given a blanket. I think Atwood's prose might be my blanket.

These stories are just about life. They are about being an educated but earthy woman, a human being, a collection of memories, hopes, dreams, comparisons, imaginings. The actual subjects almost sound ridiculous: the protagonist remembers knitting for her baby sister, she remembers an overly elaborate Halloween costume she made that went unappreciated, she tells us the story of breaking up with a boyfriend while trying to study for an upcoming exam on Browning's "My Last Duchess." She recalls living alone, living domestically, caring for her parents, being smothered by her parents, etc.

I am reduced to profanities when I try to express how much I liked this. The stories were so real, so resonant. Instead of someone trying to predict how women feel, how life works for them, she just tells you. That's what I mean by opaque. There aren't huge loping metaphors, but there's a dense block of psychological reality nonetheless.

Finally, I felt like someone was talking to me, about me. That is far different from being entertained or informed. I felt connected. I felt the way I want other people to feel when they read whatever it is I may or may not end up writing.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)